Different Type of Art Influenced by the Civil Rights Movement of the 50 60

In award of Martin Luther Rex Jr. Twenty-four hour period, we tasked curators across the state with the difficult job of choosing a unmarried work of art that they feel defines the ethos of the Civil Rights Era. Their choices present a kaleidoscopic and occasionally surprising group of works that span continents and centuries—from iconic photographs to ritual sculptural objects.

Run across the works and read the curators' insights beneath.

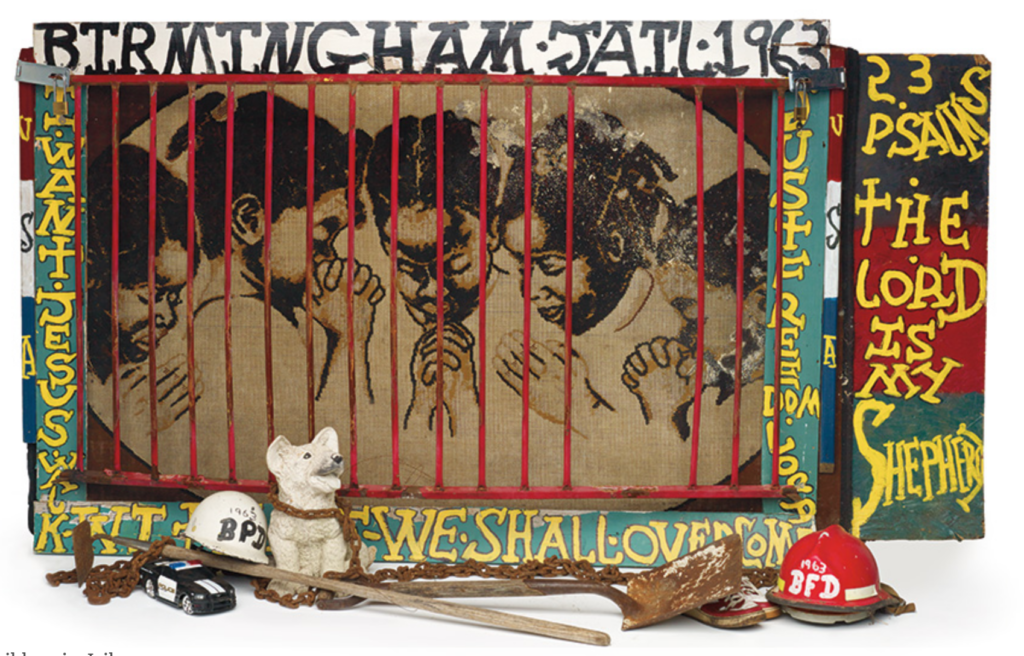

Joe Minter'sChildren In Jail (2013)

Joe Minter, Children In Jail (2013). Courtesy of Souls Grown Deep.

This gimmicky piece of work past Joe Minter reflects dorsum on Birmingham, Alabama's Children's Crusade: On May ii, 1963, more than 1,000 students skipped school and took to the streets from the doors of the 16th Street Baptist Church, and for days faced police violence and domestic dog attacks, brutal sprays of burn down hoses, and mass arrests. Ultimately, more than three,000 children took part in the direct deportment. More than 500 children were jailed by Alabama Public Condom Commissioner Bull Connor, including 75 kids crammed into a prison cell meant for 8 adults, and still others locked into animal pens at the fairgrounds for days on end. Thank you to their sacrifices and the widespread media images of brutalized black children, President Kennedy took notice, the city negotiated with Martin Luther King Jr., jailed demonstrators were freed, and Connor lost his job.

In Minter'southward multi-part sculpture, a seemingly domestic epitome of praying children is placed behind bright red bars. The violence of Birmingham's constabulary and fire departments is indicated by the strewn hats and grinning canis familiaris statue, laced with rusted chains alongside tools that Minter uses to refer to 400 years of labor and oppression inflected on Blacks by whites. A makeshift cage traps three infant dolls, representing kids in cages who fought "JUST TO B FREE."

I'm withal struck by my memory of this work, five years later seeing it at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Alabama. And, as a side annotation, I'll add that every person living in the US should visit Montgomery's Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the Equal Justice Initiative's racial injustice museum and elegiac monument to more than than iv,400 lynching victims—African American men, women, and children.

—Carmen Hermo, acquaintance curator, Brooklyn Museum

Will Count'sElizabeth Eckford of The Piddling Stone Nine (1954)

Volition Count, Elizabeth Eckford of The Petty Rock Nine (1954). Courtesy of Getty Images.

It tin be argued that in that location is no more important medium to the Ceremonious Rights motion than that of photography. The documentation of violences enacted upon black people in the south—in private lunch counters, in public parks and bridges, in educational spaces, so forth—and the subsequent mass broadcasting of this imagery, heightened public awareness of such abuses and galvanized a public's increasing demand for judicial and legislative activeness that would enforce the equality of African Americans. Indeed information technology said that the mass reproduction of Charles Moore's infamous photograph of Ceremonious Rights protesters being high-pressure h2o hosed at a spring 1963 action straight impacted the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

However equally scholars and curators similar Leigh Raiford, Maurice Berger, and Connie Choi take written, the usage, status, and function of photography during the move was much more than complicated than mere documentary realism. For instance, there was non uniformity effectually how these images were read and understood by all publics, even intra-racially; nor did all images themselves evince the larger context in which these actions took place or offer upwards the full telescopic of the movement's participants. Indeed, as Raiford argues, black people increasingly turned to photography as a tool for shaping and presenting their own images to themselves, not just an imagined white public.

Of course, photography in this moment also calls forth questions of spectacle, and that of the ethics surrounding the circulation of images that characteristic violence being enacted upon, or violated, blackness persons. When has an image served its "purpose"? How do the reproduction of these images serve to shape public consciousness over time in ways more than complex than mere "sensation"?

In this paradigm, a group of young white women and men are aroused. This is gleaned from the facts of the faces: of the menacing glares, of the mouth afraid in rage. A slight step alee of them is the target of this terror: a young blackness woman, looking forwards through her sunglasses, clutching her folder in hand.

There are the things that a photo tin can and cannot say. For example, it had always been the plan for the grouping of students called to integrate Little Rock Key Loftier School in the fall of 1957 to arrive together. Ane of the "Little Rock Nine," 15-yr-former Elizabeth Eckford had ultimately arrived at the wrong meeting place, not having received word of a shifted meeting plan. In this photograph, she makes her way through a mob of hundreds, with her gaze directed forward through her sunglasses, as she clutches her binder in mitt, alone. This mob—which includes Hazel Bryan, who shouts aspersions at her back, and the National Guard deployed to terrorize the integrating students—prevents her from entering school on this day. It would have the deployment of troops at the command of the president to allow rubber (physical) entrance for Eckford and the other viii, some weeks after.The traumatic events of this twenty-four hour period will go on to effect Eckford into her adulthood.

When I come across this photograph, I retrieve of the ordinary and the extraordinary, of youth and of bravery. How a young, ordinary girl, was forced to occupy a posture of extraordinary bravery in the face of a violence that was extraordinarily hostile and in part boggling in its ordinariness. I sit with what that means.

—Ashley James, associate curator of contemporary art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Elizabeth Catlett'sHomage To My Young Black Sisters (1968)

Elizabeth Catlett, Homage To My Immature Black Sisters (1968)

Homage to My Young Black Sisters represents the influence of hundreds of everyday young women who participated in grassroots organizing and revolutionary action during the Civil Rights era. Catlett oftentimes identified with these women because she, as well, was consistently beleaguered by the US government for her revolutionary political ties and eventually forced to relinquish her American citizenship, in 1962. The gesture of the sculpture is clear. Its clenched fist and dominant stance shouts Black Ability in the wake of Jim Crow segregation. Catlett speaks openly to her audience with this work, revealing that the pulse of the Ceremonious Rights era began with blackness women.

—Kelli Morgan, associate curator of American art, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields

Gordon Parks'southEthel Sharrieff, Chicago, Illinois (1963)

Gordon Parks, Ethel Sharrieff, Chicago, Illinois (1963).

No other visual medium defined the Civil Rights movement than documentary photography, specially the black-and-white images of male leaders, cordons of marchers under turbulent skies, or black children in their Sunday all-time blasted with M-forces past the Birmingham burn down section. Gordon Parks, i of the dandy chroniclers of the era, made the important determination to equally certificate black people in their communities, frequently in moments of peace and self-sufficiency. His "Black Muslims" series forLifemagazine was a wake-up call for many not-blackness Americans who were fascinated and alarmed by the group. Park's portraitEthel Sharieff for the magazine feature stands as an iconic image of the series and the Ceremonious Rights era. A single woman set against an army of sisters encapsulates all the resolve, communitarianism, and new consciousness the moment was brewing, without falling back on whatever proscribed clichés.

—Naomi Beckwith, senior curator, Museum of Contemporary Fine art, Chicago

Frank Bowling'southwardNighttime Journeying (1969–lxx)

Frank Bowling, Dark Journey (1969–seventy). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art.

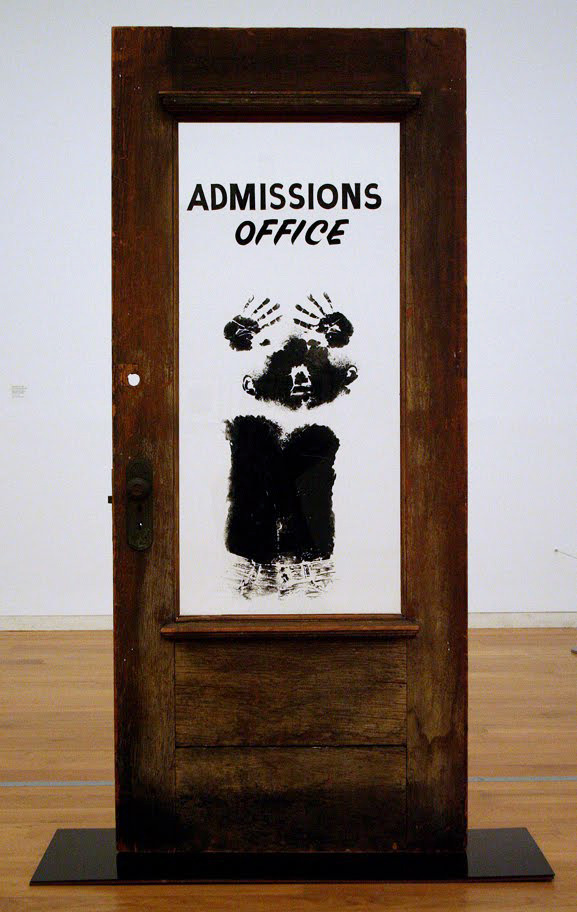

It's a tall—fifty-fifty impossible—task to summarize the Civil Rights Era with a single piece of work of art. The best I tin can do is to highlight a few of my favorites (across media) and admit to a item favorite in the Met collection. I love so many of Gordon Parks's photographs from the menses, especially Department Store, Mobile, Alabama (1956), an prototype that never loses its power. Elizabeth Catlett's Black Unity (1968) is a neat sculptural icon of the menstruum. David Hammons'due south body prints, such as The Door (Admissions Office) (1969), are difficult to surpass in their inventiveness and visceral affect. A favorite of mine at the Met is Frank Bowling'southward Night Journey (1969-70), a beautiful painting in the creative person'due south "Map" serial. Bowling masterfully employs his staining and pouring techniques to ruminate on the forced body of water journeys endured by enslaved people taken from West Africa to the Americas and West Indies.

—Randall Griffey, curator, the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

David Hammons'sThe Door (Admissions Part) (1969)

David Hammons,The Door (Admissions Function) (1969). Courtesy of Collection of Friends, the Foundation of the California African American Museum, Los Angeles.

With the ridges of fingerprints and curls of pilus even so visible in the dried black oil, a homo Rorschach examination is printed upon a transparent windowed admissions door. Paw-prints halo above the epitome of a double face; the gesture is one, often futile, fabricated in pleas for safety, one which remains important in protests of communal recognition. David Hammons's The Door (Admissions Office) (1969) not but critically comments on the blockades of academia, civil rights, and nationhood, but speaks directly to the political commitments and legacy activism of youth in the country.

This piece of work continues to reaffirm the presence of barricades and borders that remain closed merely could be easily opened, if simply for the single turn of a wrist. This work, often generously loaned by the California African American Museum, continues to be emblematic of creative interventions of the Civil Rights era and has been a part of meaning exhibitions such as "Crosscurrents: Africa and Black Diasporas in Dialogue, 1960-1980" at the Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco; "Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties" at the Brooklyn Museum, and is at present on view as a part of the international tour of "Soul of a Nation."

—Emily A. Kuhlmann, director of exhibitions and curatorial affairs, Museum of the African Diaspora

Congolese's Nkisi Nkondi (Power Figure)

Nkisi Nkondi, 19th century, Republic of Congo, Angola, Chiloango River region. Woods, plant fiber, atomic number 26, resin, ceramics, textile, pigment. Yombe artist. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Often referred to equally a power figure, nkisi was a container that held the bilongo (medicine) that purified the self and community in "Kongo" culture. This figure mediated the sacred and profane spheres, addressing social concerns and warding off evil spirits. It'southward jarring presence endured many driven nails that bind promises and seal deals. No other symbol could have encapsulated the Civil Rights movement in this country. Despite all the tribulations, progress was fabricated in archiving some of the aspirations that divers the cause at that fourth dimension.

—Ndubuisi C. Ezeluomba, Françoise Billion Richardson curator of African art, New Orleans Museum of Art

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Desire to stay ahead of the fine art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to go the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that bulldoze the chat frontward.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/artworks-that-define-the-civil-rights-era-1755375

0 Response to "Different Type of Art Influenced by the Civil Rights Movement of the 50 60"

Post a Comment