what happens to information when it reaches the brain

Tin can Your Encephalon Really Be "Full"?

Neuroimaging aids investigation into what happens in the encephalon when we try to remember information that's very similar to what we already know

The following essay is reprinted with permission from The Chat, an online publication covering the latest research.

The brain is truly a marvel. A seemingly countless library, whose shelves business firm our most precious memories as well as our lifetime's knowledge. But is there a signal where information technology reaches capacity? In other words, can the brain be "total"?

The respond is a resounding no, because, well, brains are more sophisticated than that. A study published in Nature Neuroscience earlier this year shows that instead of just crowding in, sometime information is sometimes pushed out of the brain for new memories to course.

Previous behavioural studies take shown that learning new information tin lead to forgetting. But in this report, researchers used new neuroimaging techniques to demonstrate for the start time how this effect occurs in the brain.

The experiment

The paper's authors set out to investigate what happens in the brain when nosotros try to remember information that's very similar to what nosotros already know. This is important because like information is more than probable to interfere with existing knowledge, and it's the stuff that crowds without existence useful.

To practice this, they examined how brain action changes when we try to remember a "target" memory, that is, when we endeavour to recall something very specific, at the same time as trying to remember something similar (a "competing" memory). Participants were taught to associate a single word (say, the word sand) with 2 dissimilar images—such as one of Marilyn Monroe and the other of a hat.

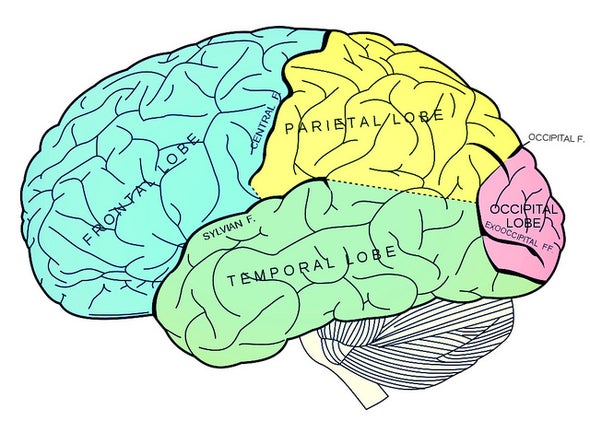

They found that every bit the target memory was recalled more often, brain action for it increased. Meanwhile, encephalon activeness for the competing memory simultaneously weakened. This modify was most prominent in regions near the front of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex, rather than central memory structures in the middle of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is traditionally associated with retentivity loss.

The prefrontal cortex is involved in a range of complex cognitive processes, such equally planning, conclusion making, and selective retrieval of memory. Extensive enquiry shows this part of the brain works in combination with the hippocampus to recall specific memories.

If the hippocampus is the search engine, the prefrontal cortex is the filter determining which memory is the most relevant. This suggests that storing information solitary is not enough for a practiced memory. The brain likewise needs to be able to access the relevant information without being distracted by similar competing pieces of information.

Amend to forget

In daily life, forgetting actually has clear advantages. Imagine, for instance, that you lost your depository financial institution card. The new carte du jour you lot receive will come with a new personal identification number (Pin). Research in this field suggests that each time y'all remember the new Pin, you gradually forget the onetime 1. This process improves access to relevant information, without old memories interfering.

And virtually of united states of america volition be able to place with the frustration of having former memories interfere with new, relevant memories. Consider trying to think where you parked your car in the same carpark yous were at a calendar week earlier. This blazon of retentivity (where you are trying to remember new, but similar data) is especially susceptible to interference.

When we learn new data, the brain automatically tries to incorporate it inside existing information past forming associations. And when we call up information, both the desired and associated just irrelevant data is recalled.

The majority of previous research has focused on how we acquire and recollect new information. But electric current studies are outset to identify greater accent on the conditions under which nosotros forget, as its importance begins to exist more appreciated.

The curse of memory

A very pocket-sized number of people are able to remember almost every particular of their life in groovy particular; they accept hyperthymestic syndrome. If provided with a date, they are able to tell you where and what they were doing on that particular 24-hour interval. While it may sound like a boon to many, people with this rare condition often find their unusual ability burdensome.

Some report an inability to think virtually the present or the hereafter, because of the feeling of constantly living in the past, caught in their memories. And this is what we all might experience if our brains didn't have a machinery for superseding data that'south no longer relevant and did indeed make full up.

At the other cease of the spectrum is a phenomenon chosen "accelerated long-term forgetting", which has been observed in epilepsy and stroke patients. As the proper name suggests, these people forget newly learnt information at a much faster charge per unit, sometimes inside a few hours, compared to what'due south considered normal.

It'southward believed this represents a failure to "consolidate" or transfer new memories into long-term retentivity. Just the processes and bear on of this form of forgetting are even so largely unexplored.

What studies in this area are demonstrating is that remembering and forgetting are two sides of the same money. In a sense, forgetting is our brain's way of sorting memories, so the most relevant memories are ready for retrieval. Normal forgetting may even be a safety machinery to ensure our encephalon doesn't become too full.

This commodity was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-your-brain-really-be-full/

0 Response to "what happens to information when it reaches the brain"

Post a Comment